The Four Seasons, a silent natural history masterpiece produced and directed by Raymond Ditmars, began its successful run at the Rialto Theatre on Times Square, New York City on September 25, 1921.

As its title suggests The Four Seasons - a reel per season - documented the effects of the changing seasons on animal life. The formula has been repeated in countless natural history programmes right up to the present day, but when Ditmars first put the idea on celluloid it was a sensation.

British movie mogul Charles Urban edited the footage together for the theatrical release. Urban told the New York Tribune that the production ‘brought together hundreds of pictures of Nature, much like a man traveling through the woods at different times of the year, first seeing one thing and then another ... It is a wonderful story which Nature tells each year, and this we have tried to tell in “The Four Seasons.”’

As its title suggests The Four Seasons - a reel per season - documented the effects of the changing seasons on animal life. The formula has been repeated in countless natural history programmes right up to the present day, but when Ditmars first put the idea on celluloid it was a sensation.

British movie mogul Charles Urban edited the footage together for the theatrical release. Urban told the New York Tribune that the production ‘brought together hundreds of pictures of Nature, much like a man traveling through the woods at different times of the year, first seeing one thing and then another ... It is a wonderful story which Nature tells each year, and this we have tried to tell in “The Four Seasons.”’

Despite competing for column inches with Charlie Chaplin’s The Idle Class which opened the same week, The Four Seasons was widely praised.

The New York Times called the film, ‘one of the worth-while works of the year’ and was impressed with how Ditmars and Urban had managed to make an apparently dull subject interesting and engaging for the audience. The paper noted that although the films followed the growth of a selection of animals through each season, at the same time a new character was introduced in each reel to ‘freshen the interest’. In addition, ‘with some departure, perhaps, from the strictly pedagogic point of view, but greatly to the enrichment of the film as entertainment, the makers of the picture have selected subjects, which by their novelty, oddity and beauty, may be counted upon to have a popular appeal.’ The only negative note concerned the photography which was ‘satisfactory’ but left ‘room for improvement’.

For Life magazine, ‘the acting of the frogs’ was ‘truly remarkable’.

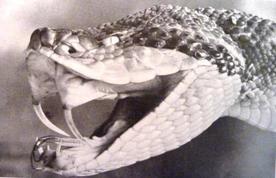

As with his previous masterwork, The Living Book of Nature, Raymond Ditmars often took time out from looking after reptiles at the Bronx Zoo to narrate the silent pictures himself and grew hoarse in the process!

The New York Times called the film, ‘one of the worth-while works of the year’ and was impressed with how Ditmars and Urban had managed to make an apparently dull subject interesting and engaging for the audience. The paper noted that although the films followed the growth of a selection of animals through each season, at the same time a new character was introduced in each reel to ‘freshen the interest’. In addition, ‘with some departure, perhaps, from the strictly pedagogic point of view, but greatly to the enrichment of the film as entertainment, the makers of the picture have selected subjects, which by their novelty, oddity and beauty, may be counted upon to have a popular appeal.’ The only negative note concerned the photography which was ‘satisfactory’ but left ‘room for improvement’.

For Life magazine, ‘the acting of the frogs’ was ‘truly remarkable’.

As with his previous masterwork, The Living Book of Nature, Raymond Ditmars often took time out from looking after reptiles at the Bronx Zoo to narrate the silent pictures himself and grew hoarse in the process!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed