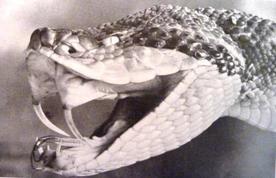

The bushmaster's reputation for being the world's largest viper - and thus perhaps among the most fearsome of nature's beasts - is somewhat undermined by its shocking fragility in captivity.

This was something, Bronx Zoo curator Raymond Ditmars learnt the hard way, with a succession of specimens arriving at the reptile house in the first two decades of the twentieth century only to pass away within months, even weeks, of going on exhibition.

The bushmaster is a remarkably sensitive and fragile snake, and unless caught and handled gently was liable, quite literally, to break. The preferred method for capturing venomous serpents in Ditmars’s day—noosing them at a safe distance—snapped the bushmaster’s delicate backbone like glass. Like other wild-caught snakes, bushmasters were also susceptible to parasitic infestation, often by tiny worms called pentastomids. It would take many decades more before the secrets of keeping a Lachesis muta going, if not thriving, in captivity.

This was something, Bronx Zoo curator Raymond Ditmars learnt the hard way, with a succession of specimens arriving at the reptile house in the first two decades of the twentieth century only to pass away within months, even weeks, of going on exhibition.

The bushmaster is a remarkably sensitive and fragile snake, and unless caught and handled gently was liable, quite literally, to break. The preferred method for capturing venomous serpents in Ditmars’s day—noosing them at a safe distance—snapped the bushmaster’s delicate backbone like glass. Like other wild-caught snakes, bushmasters were also susceptible to parasitic infestation, often by tiny worms called pentastomids. It would take many decades more before the secrets of keeping a Lachesis muta going, if not thriving, in captivity.

In April 1955 - 60 years ago this month - one more bushmaster was added to the long tragic list of zoo deaths, in this case it was the National Zoological Gardens, Washington, DC. A specimen captured six months before in Trinidad (Ditmars himself's most fruitful tropical hunting grounds during the late 1930s) died after refusing food.

"From his original girth (about the size of a man’s wrist) he shrunk gradually into a streamlined semi coma from which he was barely able to rouse himself," reported The Washington Post and Times Herald. "He simply wasted away," said Zoo Director William M. Mann (a friend and colleague of Raymond Ditmars), who had been wont to visit him almost daily in the futile hope that the snake had relented in his resolve to starve himself to death.

According to the papers, in his last days the snake "was barely able to rouse himself to take a bit of water—his sole concession to captivity. Over the weekend, however, he writhed his last."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed